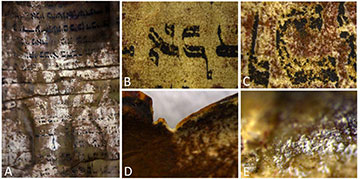

The ancient Hebrew parchment under study revealed multiple different types of degradation, including discoloration and staining (A), fading ink (B), corroded ink (C), fractured edges (D) and white, powdery deposits (E). [Image: Courtesy of the authors] [Enlarge image]

Multiple optical imaging techniques applied to an ancient Jewish parchment have revealed important clues to its origins and history, according to researchers in Romania who conducted the studies (Front. Mater., doi: 10.3389/fmats.2020.601339).

The nondestructive techniques that the team used on the significantly degraded parchment—multi- and hyperspectral imaging (MSI/HSI), X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)—are well known in the field, notes co-author Luminita Ghervase of Romania’s National Institute of Research and Development for Optoelectronics (INOE 2000). “What was missing were specialized studies [on ancient parchments],” she says. “We consider ourselves lucky that the owner [of the study parchment] trusted us with this very special object.”

Imaging to guide conservators, restorers

The information provided by the imaging studies, Ghervase says, could guide conservators and restorers who would work to save this and similar artifacts. She also notes that INOE 2000 has 20 years of experience working with cultural-heritage artifacts, many of them archaeological or ancient materials.

The main objective of the team’s multi-analytic approach, according to Ghervase, was to extract key information on the parchment manufacturing technique, as well as the original materials used and their degeneration. “One of the most interesting finds was that both the parchment and the text had suffered interventions during the lifetime of the scroll, which we were able to identify and map,” she says.

Ghervase points out that an algorithm the research team used to identify different component materials, such as ink traces, might also be used to infer original shapes of letters on the severely damaged scroll. “This could be a most helpful tool if reconstruction of the original text will be a desired goal in the future,” Ghervase says.

Production of a ritual parchment

The parchment scroll contains chapters from the Book of Esther in the Hebrew Bible, Ghervase says. The book tells of the salvation of the Jewish people during the First Persian Empire, and it is read during the Jewish holiday of Purim.

Strict religious rules that guided production of these ritual parchments provided the INOE 2000 researchers with some baseline information for their studies. For example, the team knew that the parchment would have been made from the skin of a kosher animal—goats, sheep, or calves, depending on geographic location.

What’s more, the researchers write, the rules dictated that sacred parchments were to be inscribed in Hebrew, on one side only, in square text with black ink. Treatment or repairs were limited to parchment patches to be placed on the outside of the document. If the scroll became too damaged or degraded, it was to be hidden away or buried.

“Each of the objects that come to our lab are allocated a fair amount of time not just for the actual analysis and interpretation of results, but also for the anamnesis of the object, which includes gathering all possible information—from a discussion with the owner or from specialized scientific literature,” Ghervase says. “When needed, we also work with experts in complementary fields to best interpret our results. “

Teasing out a conservation history

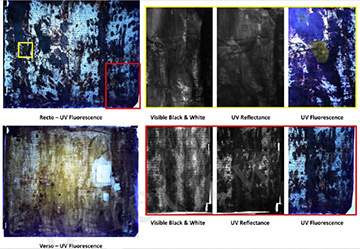

UV fluorescence and reflectance imaging revealed both evidence of interventions after the parchment’s original creation (dark blotches), and coloration that could be tied to zinc-based methods used to create the parchment in the first place (yellow-green areas on verso). [Image: Courtesy of the authors] [Enlarge image]

With MSI, the researchers say they were able to develop detailed documentation of the overall conservation state of the ancient Jewish scroll. For example, UV fluorescence (UVF) and UV reflectance (UVR) acquisition modes revealed dark blotches on the manuscript—areas of high UV absorption that they say probably result from more recent interventions. Oils or natural resins used in repairs, the team explains, will not fluoresce until a certain state of degradation has occurred.

Yellow-green UVF on the back side of the document is consistent with zinc oxide, and the literature indeed indicates that cooked zinc was used to prepare the animal skins, the researchers say. Purple red fluorescence on other areas of the document could indicate other treatments or microbial or fungal attacks.

Scratches revealed at wavelengths of 2400 nm on the writing side of the document, the team believes, could be the result of making the parchment itself or later cleaning or error correction of the text. However, Jewish law would have forbidden a religious text being transcribed on an erased parchment, the researchers note.

Highlighting ancient text

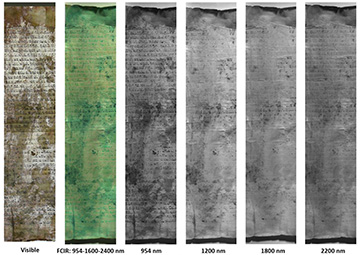

Use of HSI in the shortwave infrared region showed that text on the scroll starts to lose opacity at longer wavelengths, becoming almost transparent at 1200 nm. The finding is consistent with iron gall ink used on ancient parchment scrolls, the researchers say.

Different wavelength values in hyperspectral imaging suggested the use of different inks to create and later restore the manuscript text. [Image: Courtesy of the authors] [Enlarge image]

But in other areas of the document—notably, dark patches revealed with UVR/UVF imaging-- the ink retains its opacity at even 1800 nm. This may indicate the use of carbon black ink, they say, another finding consistent with later conservation efforts. The researchers stress, however, that carbon black ink might also have been used for letter correction.

Tracing history with trace elements

Analysis of XRF spectra from the document, according to the study, shows trace elements consistent with iron gall inks, typically made from a mixture of iron, sulfate, and gallic acid. But the team also detected trace amounts of silver, which the authors say may have resulted from a disinfection procedure, as well as chlorine that might have resulted from washing the parchment in seawater or residue from salts used to dehair the skin.

Zinc presented the most intense lines for all spectra in the XRF analysis, the team says. Its highest intensities on white areas of the manuscript suggest a bleaching process, though they also note that zinc chloride has been used by restorers to increase gelatin flexibility of parchments. And a certain amount of zinc might come from the ink components, too, they say.

Calcium lines are evident in all spectra obtained, the research team notes, which could indicate a liming process for depilating animal skin, or it might be a clue to the manuscript’s origin. Lime was the preferred process for parchments of western origins, they say, while enzymatic processes were more typically used in eastern areas.

Studying deterioration in pursuit of conservation

Finally, FTIR analysis gave an in-depth view of the deterioration rate of the collagen materials in the parchment as seen in an amide II band shift to lower wavelengths, the researchers say. This imaging modality also revealed the presence of gypsum, tannins, and oils consistent with Jewish preparation techniques as well as other materials that indicate later conservation/restoration strategies.

Overall, the researchers say, their study brings new knowledge of cultural-heritage objects that have “multiple values from a historical, cultural, and also from a religious point of view.” The findings, they conclude, should be of “great interest for conservation and restoration practitioners by offering valuable information for the restoration procedure for this highly degraded Jewish ritual parchment.”