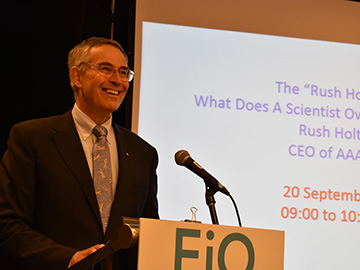

AAAS CEO Rush Holt, in a special session at FiO 2017, asked the question “What Does a Scientist Owe Policymakers?”

Given what seems an ever more polarized and uncertain political environment, scientists increasingly grapple with the need to persuade policymakers and the public about the importance of the work that science does. In a morning session at the 2017 Frontiers in Optics meeting, Rush Holt, the CEO of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), suggested that scientists trying to make that case often end up “communicating the wrong thing.”

The dilemmas of a “post-fact” world

In introducing Holt at a standing-room-only morning session (aptly titled “The Rush Hour”), OSA President Eric Mazur noted that the speaker, who is also a physicist, had “spent 16 years in the thick of it all” as a U.S. congressman from the state of New Jersey before taking the reins at AAAS. Holt quipped that when asked by people what it was like to go from Congress to AAAS, he commonly answers, “It’s nice to feel needed.” But Holt’s talk had a serious theme, rooted in “deep concerns” about the place of science in U.S. and world society, and where it’s going.

“Polls will say that 90 percent of people in this country and other countries think that science is important, and they say they love it,” Holt said. “But despite these positive words, I think there’s reason for concern in what we now have come to call a ‘post-fact’ world.” He cited particular examples from the U.S.—such as the public’s lack of appreciation of the potential impact of immigration restrictions on scientific competitiveness—and also, of course, persistent pressure on funding. The focus of that pressure “varies from year to year, or from month to month,” Holt acknowledged. “But there’s always something under threat.”

From facts to process

Holt sees the problem as “in large part our fault”—and suggests that it’s tied to the tendency to focus on reporting facts and results, rather than science as a process. “We are too hung up on facts,” he said. “We often behave as if science is more believable if it’s presented without uncertainty.” Yet he stressed that uncertainty and the ongoing process of testing and revising “revealed wisdom” lie at the very core of science. “The source of the power of the method,” he said, “is that there’s always a patent clerk in Switzerland who knows more than we do, and will demonstrate to us that everything we’ve based our work on is wrong.”

Holt at FiO 2017.

Communicating science in this way—as tentative, self-correcting and always imbued with some uncertainty—has “wide-ranging benefits,” according to Holt. One could lie in increased public trust of scientists generally. But Holt also sees an ethical dimension to the issue.

“We haven’t stopped to think about the ethics of science communication,” he maintained. “Science is enormously powerful, not just for scientists but for nonscientists. We have denied the public that understanding. And that’s unethical.” The goal of “science literacy,” he suggested, should be not a data-dump of facts, but instead arming the public with the ability to “think like a scientist”—and to access a method of inquiry that history has shown to be “the most useful way of thinking and the best way of avoiding being deceived—by others or by ourselves.”

Communicating the virtues of uncertainty

A scientist who has not grasped this need, and focused instead on simply feeding the public a stream of facts, “may not only have failed to communicate effectively,” said Holt, “but may have done real damage to the policymaking process—and ultimately, real damage to society.” That’s because, he suggested, society badly needs to understand, and embrace, the idea and process of science given the many challenges the world faces.

Holt summed things up by quoting an aphorism of the early-20th-century judge and legal philosopher Learned Hand: The spirit of liberty is the spirit that’s not too sure it’s right. “A scientist can understand that,” said Holt. “All the public should understand it, too—that the goal is not certainty, but self-correction.”

“Our challenge,” he concluded, “is to find a way to communicate this bigger lesson of science.”

A video of the complete “Rush Hour” session can be found on OSA’s Facebook Page.