In early June, the European Commission (E.C.) finally unveiled the details of its ninth Framework Programme—the proposal for European Union (E.U.) research and innovation spending that will govern the E.U.’s seven fiscal years from 2021 to 2027.

Dubbed Horizon Europe, the newly released plan offers a substantial uptick in funding relative to its predecessor, Horizon 2020, the E.U. program laying out the 2014-to-2020 R&D budget. Horizon Europe also differs from the previous program in placing a substantially greater emphasis on entrepreneurship and innovation, and in adopting an approach built around Europe-wide research and innovation “missions” tied to major societal problems and challenges.

But the proposal has already drawn fire from European universities, which view even the increased E.U. funding commitment envisioned by the plan as woefully inadequate. And the universities also fear that Horizon Europe’s new, explicit emphasis on innovation and entrepreneurship could lead to the underfunding of basic (read: academic) research.

Seven years, 100 billion euros

The E.C. has touted its seven-year spending plan as the E.U.’s “most ambitious research and innovation program yet.” The overall plan envisions €100 billion to be spent over the 2021–2027 period: €94.1 billion through the Horizon Europe framework; €3.5 billion through the InvestEU Fund, a program to mobilize public and private investment in sustainable energy, small- and medium-sized enterprises and other areas; and €2.4 billion through the Euratom research and training program, which focuses on nuclear safety and protection. The total expenditure represents a 22 percent jump from the previous seven-year E.U. funding tranche under Horizon 2020 and related programs.

Even with that increase, though, E.U. funding is just one piece of the puzzle. “The EU funding is important, but it’s only part of what European nations spend on R&D overall,” says Tom Hausken, the senior industry advisor for The Optical Society (OSA). “The rest comes from national governments—particularly Germany, France and the U.K.”

Hausken also notes that the E.U. funding pot is dwarfed, for example, by United States federal expenditures to support research. “The U.S. government spends nearly US$80B for non-military R&D in one year alone,” he observes, “and about US$140B for all federal R&D per year.” That’s well above the E.U. allocation for the entire seven-year period covered by Horizon Europe.

Missions and pillars

As had been widely expected, the Horizon Europe plan largely rests on previous recommendations that the next Framework Programme adopt a “mission-driven” approach. In one particularly influential 2017 study, Lab–Fab–App: Investing in the European Future We Want (the “Lamy report”), for example, a high-level group of representatives from academic and industrial research argued that the ninth Framework Programme should “set research and innovation missions that address global challenges and mobilize researchers, innovators and other stakeholders to realize them.”

A follow-up report published in February 2018, Mission-Oriented Research & Innovation in the European Union, laid out specific recommendations on how to increase the impact of E.U. research spending “through mission-oriented policy.” The report specifically cited the U.S. Apollo program to put a human on the moon as an example of the power of a mission-driven approach both to provide inspiration and to mobilize resources to solve a problem.

Within that mission-driven framework, Horizon Europe is designed around three “pillars.”:

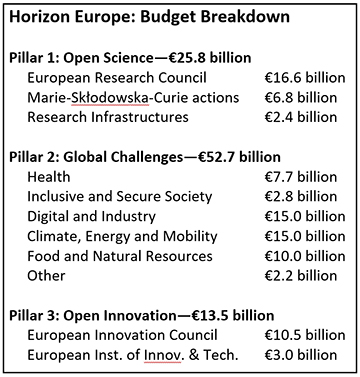

- Pillar 1, “Open Science,” provides a total of €25.8 billion in funding for fundamental research and grants for research mobility, through the European Research Council (ERC) and the highly successful Marie-Skłodowska-Curie fellowships for students, postdocs and other researchers.

- Pillar 2, “Global Challenges,” is the mission-driven piece of the program, and will receive a significant €52.7 billion share of the total Horizon Europe funding. That expenditure will be split across five “clusters” targeting broad social missions related to health; inclusive and secure societies; digital and industry development; climate, energy and mobility; and food and natural resources.

- Pillar 3, “Open Innovation,” will target €13.5 billion to “make Europe a front runner in market-creating innovation.” A key component will be the creation of a European Innovation Council tasked with of fering “a one-stop shop for high potential and breakthrough technologies and innovative companies with potential for scaling up.”

Finally, in addition to the three pillars, Horizon Europe includes a €2.1 billion funding line for “strengthening the European research area.”

Pushback from academic researchers

The Horizon Europe budget plan spurred an immediate, and not entirely welcoming, response from the European academic community—embodied most forcefully in a joint statement from 14 separate university groups representing hundreds of academic institutions. The biggest bone of contention is the amount of funding envisioned for the seven years. Numerous stakeholder groups and white papers (including the Lamy report) had argued that the ninth Framework Programme needed to at least double the money pot from the previous program, to a level of €160 billion or more. That’s more than €60 billion above what the Horizon Europe plan has actually delivered.

The universities also object to the allocation of the funds, arguing that the relatively minor increases for the Marie-Skłodowska-Curie actions and the ERC undervalue the successful track record of these programs in advancing European research. And the joint statement argues for a more balanced distribution of funds across the five clusters in pillar 2, in recognition that all five clusters represent “the most pressing challenges our societies are facing.”

Perhaps the universities’ most notable stated concerns, however, relate to Horizon Europe’s explicit emphasis on industry, innovation and technology transfer. For example, the joint statement argues that the role of universities in the European Innovation Council to be established under the plan’s pillar 3 “must be amplified and recognized,” and that “linkages between research, innovation and education in Horizon Europe must be improved.”

“Industry’s short-term interest should not prevail over society’s long-term benefits from Horizon Europe,” the university statement concludes in boldface type. “Close-to-market activities should be complemented explicitly with fundamental research.”