Grégoire Ribordy [Image: Courtesy of ID Quantique]

In the second day of OSA’s Quantum 2.0 conference, the focus shifted from quantum computing to other aspects of quantum technology—particularly quantum communications and quantum sensing. On that note, Grégoire Ribordy, the founder of the Switzerland-based quantum crypto firm ID Quantique, looked at how quantum technologies are being employed for the long-term challenges in data security posed by quantum computing itself.

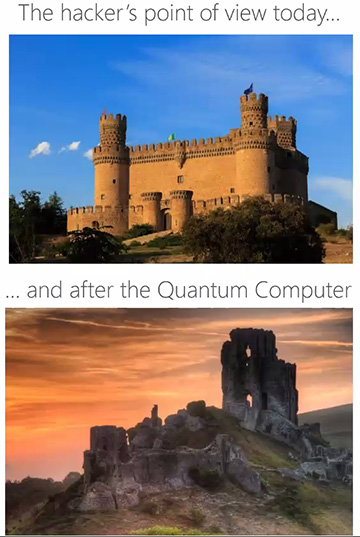

Storming the castle

ID Quantique has a long pedigree in quantum technology; the company has been in business since 2001. In retrospect, Ribordy said, “we were really crazy to start a company in quantum technology in 2001 … It was way too early.” But the firm forged ahead and has now developed a suite of applications in the data-security space.

Ribordy stressed that—“especially over the past few months”—it’s become increasingly clear that digital security, and protecting digital information against hacking, is extremely important. Classical cryptography assembles a set of techniques for hiding information from unauthorized users, which Ribordy compared to “building a castle” around the data.

The problem, however, is that after quantum computers become reality, one application for them will be to crack the cryptography systems that are currently in use. When that happens, said Ribordy, “the walls we have today won’t be able to protect the data anymore.” The best cryptography techniques for avoiding that baleful outcome, he suggested, are those that themselves rely on quantum technology—and that can provide robust protection, while still allowing the convenience of the prevailing classical private-key encryption systems.

[Image: Grégoire Ribordy/OSA Quantum 2.0 Conference]

Of x, y and z

Just how much one should worry about all of this now—when quantum computers powerful enough to do this sort of cracking still lie years in the future—depends, according to Ribordy, on three factors. One, which he labeled factor x, is how long you need current data to be encrypted—perhaps only a short time for some kinds of records, decades for other kinds. The second, y, is the time that it will take to retool the current infrastructure to be transformed into something quantum-safe. And the third, z, is how long it will actually take for large-scale, encryption-breaking quantum computers to be built.

If x and/or y are longer than z, he suggested, we have a problem—and there’s “a lot of debate today” surrounding just what the values of these variables are. One of ID Quantique’s services is to take clients through a “quantum risk assessment” that attempts to suss out how long they need to protect their data, and what the implications are for their cryptography approach.

Supercharging random numbers

Ribordy cited three key components to effective long-term quantum encryption. One, and perhaps the oldest, is quantum random number generation (QRNG) to build security keys, whether classical or quantum. A second is something that Ribordy called “crypto-agility.” (“You don’t hard-code cryptography,” he explained. “Instead, you want to upgrade it whenever a new advance comes.”) And the third component is quantum key distribution (QKD), which is a technique still under active development, but which is already being deployed in some cases.

On the first component, Ribordy noted that ID Quantique has been active in QRNG since 2014, when the idea arose of using mobile-phone camera sensors as a source for QRNs. These arrays of pixels, he said, can provide both “large rates of raw entropy” (an obvious necessity for true randomness), and an industry-compatible interface. He walked the audience through the company’s efforts to create a low-cost (CMOS-based), low-power, security-compliant chip for QRNG—beginning with early experiments using a Nokia phone and moving through the required efforts at miniaturization, engineering for stability and consistency, and avoiding such pitfalls as correlations between the different camera pixels, which would degrade the randomness of the output.

The result, Ribordy said, is a QRNG chip that has recently been added to a new Samsung mobile phone—appropriately named the Galaxy A71 Quantum—that is now available in the Republic of Korea. And the chip is not just window dressing—a Korean software company partnered with Samsung to create apps for pay services, cryptocurrency services and other features that rely on random numbers, and that use the ID Quantique chip to get high-quality instances of them.

Grégoire Ribordy, at the OSA Quantum 2.0 conference.

“We think this is very important,” said Ribordy, “because it shows that quantum technologies can be industrialized and integrated into applications.”

The road to QKD

In terms of such industrialization, another security application, quantum key distribution (QKD) is not as advanced as QRNG, according to Ribordy—but he argued that the experience of QRNG bodes well for QKD’s commercialization path. One issue for QKD is the short distance that such secure links can exist in fiber before quantum bit error rates become too high, though Ribordy pointed to recent paper in Nature Photonics in which “practical QKD” was demonstrated across a fiber link of 307 km.

Ribordy noted a number of areas of particular activity in the QKD sphere. One active area of interest, for example, is developing network topologies that play especially well with QKD. ID Quantique is also working with SK Telecom in the Republic of Korea on how QKD can be integrated into the optical networks underlying next-generation, 5G wireless. In these circumstances, the proverbial “last mile,” operating at radio frequencies, can only be secured with traditional cryptography, but using QKD on the optical part of the communication chain will make the network as a whole more secure.

A number of other projects are in the works as well, Ribordy said, including a European project, Open QKD, the goal of which is to “prepare the next generation of QKD deployment in Europe.” And large-scale deployment projects are afoot in China as well.

The presence of these diverging global efforts prompted a question in the Q&A session that followed Ribordy’s talk—just how open are these QKD markets? Ribordy noted that, in the near term “they are closing down … Since quantum is a new industry, every country or region would like to be a player.” The Chinese QKD ecosystem, he suggested, is “completely cut off—there is kind of a Galapagos effect,” and Europe also is starting to become a more closed ecosystem in the QKD arena. Ribordy views this as a “sign of market immaturity,” however, and believes things will become more open again in the future with efforts toward certification and standardization.