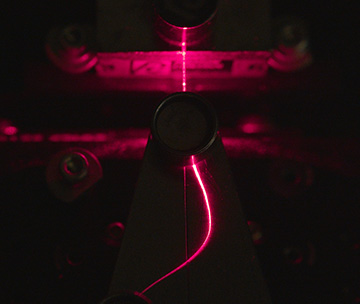

The cellulose-based optical fiber from a VTT team was able to guide light across short distances—albeit with significant light leakage in visible wavelengths. [Image: VTT]

A research team at Finland’s VTT Technical Research Center has demonstrated optical fibers made of cellulose—in essence, waveguides from wood (Cellulose, doi: 10.1007/s10570-019-02882-3). While the resulting, rather lossy fibers are unlikely to find a home in mainstream fiber domains like telecom, the researchers believe that they could ultimately prove useful in moisture detection and other niche sensing applications.

An environmentally reactive material

Optical fiber hems in light through the phenomenon known as total internal reflection. A fiber core—typically ultrapure silica glass—with a relatively high refractive index is surrounded by a layer of cladding with a somewhat lower refractive index. Laser light fired into the end of the fiber core propagates down the fiber, bouncing off of the boundary between the high-index core and the low-index cladding.

The VTT team, led by senior scientist Hannes Orelma, thought there might be space for cellulose, the organic polymer that forms a key structural component of wood and green plants, as an optical-fiber material. One reason is that the chemical processes involved in working with cellulose make it amenable to tweaking the refractive index. Cellulose also absorbs water and reacts actively (and often reversibly) with other substances, raising the possibility for sensor applications. And the material is biodegradable, which points to potential environmentally responsible use in disposable sensors.

Spinning out cellulose fiber

To make the cellulose fiber, Orelma’s team began with bleached softwood kraft pulp from a commercial mill in central Finland. After air-drying the pulp, the researchers popped it into a Waring blender to break it down, and then dissolved it in acetate to create a sort of cellulose slurry. They spun this into lengths of fiber core using a lab-scale wet-jet spinner, and, after air-drying the fibers, coated them in a cladding layer of lower-index, commercially purchased cellulose acetate.

When they hooked up the cellulose fiber to a length of conventional fiber carrying an optical input, the team found that the fiber was able to guide light ranging from 500 to 1400 nm in wavelength. The cellulose fiber had some difficulty holding onto visible light, which could be seen leaking through the cladding (see image at top of story); its best performance seemed to lie in the infrared band from around 800 to 1300 nm. Even there, however, the fiber showed steep attenuation of light, with minimum attenuation of a whopping 5.9 dB/cm at 1130-nm wavelengths and 6.3 dB/cm at 1300 nm.

Moisture-sensing possibilities

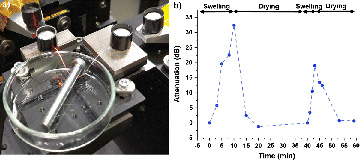

The researchers used a simple experimental setup (left) to show that the fiber’s attenuation dramatically increased with exposure to water (right). This, the team believes, shows promise for its use in moisture-detection applications. [Image: H. Orelma et al., Cellulose, doi: 10.1007/s10570-019-02882-3 (2019); CC-BY 4.0] [Enlarge image]

Despite these lossy numbers, the researchers found evidence for possible use of cellulose fiber in sensing applications. They positioned a fiber length of around 76 mm (again tied to conventional optical fibers that provided an input signal) above a container of water. When around a 20-mm length of the cellulose fiber was submerged, it started to absorb water and swell, and its attenuation statistics immediately started to climb, with the attenuation rising by more than 30 dB in the space of 10 minutes. After 20 minutes of drying time, the attenuation returned to normal.

The experiments, the team believes, suggest good potential for the material as a water sensor—for example, for picking up changes in moisture levels in buildings. And cellulose’s easy modification by other substances might, the researchers suggest, open other sensing possibilities as well. “The R&D is still in its initial phases,” team leader Orelma said in a press release accompanying the work, “so we do not yet know all the applications the new optical fiber could lend itself to.”