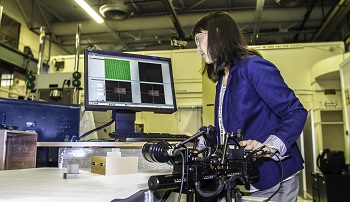

LLNL postdoctoral researcher Amanda Wu images a 3-D-printed part using digital image correlation. Credit: Julie Russell/LLNL

Additive manufacturing, better known as 3-D printing, is gaining popularity as a method for creating customizable macroscopic structures from microscopic precursor materials. The International Space Station's 3-D printer has built its own replacement part in space, physicians are printing tiny devices for spine and knee surgeries, and hobbyists are making everything from jewelry to musical instruments.

For critical applications, scientists and engineers need to assess whether their 3-D-printed objects harbor residual stresses that could lead to deformation or failure. Researchers at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (USA) recently demonstrated that a technique called digital image correlation could spot residual stresses in objects that were 3-D-printed from stainless steel powder (Metall .and Mater. Trans. A, doi:10.1007/s11661-014-2549-x).

In the 3-D-printing method known as powder-bed fusion, the printer deposits thin layers of powder on a substrate and fuses the materials together with a laser. The rapid cycles of heating and cooling as the printer builds up these layers creates localized expansion and contraction of the part, and internal stress may build up in the material.

The researchers, led by postdoctoral engineer Amanda Wu, built 3-D shapes using a variety of laser powers (100 to 400 W) and laser-processing speeds (400 to 1,800 mm/s). Using a two-camera setup, the team imaged the shapes before and after they were removed from the original build plate. A software package compared the before-and-after images for stress-related deformation of the parts.

The Livermore team checked its image-correlation results against studies of the manufactured parts using neutron diffraction, a highly accurate and non-destructive technique. Neutron diffraction is not very practical for most people doing 3-D printing, however, because the technique requires high-energy neutron sources that few laboratories possess.

The digital image correlation results agreed well with those from the neutron-diffraction tests. In addition, the researchers found that an increase in laser power and speed in the 3-D printer helps to reduce the residual stress inside the printed parts.